Major Scales and Keys

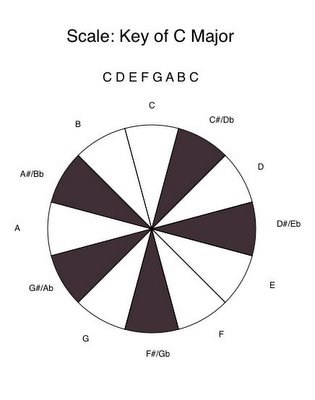

In music, a scale is a group of "allowed" notes in a certain key. For example, in the key of C major, the allowed notes are C, D, E, F, G, A, B, and, again, the next higher C. The notes of C# (C sharp), Eb (E flat), F#, Ab, and Bb are not officially allowed.

The notes that aren't allowed in C major are the black keys on a piano. You can play a C major tune without ever touching a black key.

The notes that aren't allowed in C major are the black keys on a piano. You can play a C major tune without ever touching a black key.(Each black key has two names, by the way. For example, the F# key is also the Gb key. F# and Gb are said to be enharmonics of one another: they're the same note called by two different names.)

Notice in the diagram that the disallowed notes in black are not evenly distributed around the circle of the octave. Nor is the octave circle symmetrical. It would possess a form of symmetry if, for instance, you made the F note black, or if you made the F#/Gb note white. But there is no way to distribute five black, disallowed notes and seven white, allowed notes around an octave circle of 12 notes and have the result be either evenly distributed or symmetrical.

You can mentally rotate this C major octave circle, along with the associated note names, to any of 11 different positions other than the one shown. For example, you can imagine moving, say, the note of E to the top of the circle, such that E tries to be the so-called tonic or root note of a major scale.

But if you do it that way, the pattern of black, disallowed notes does not match up with the original pattern. In the original pattern, the "next" note after the "top" note of C, which is C# (moving clockwise), is black. But now, the "next" note after the "top" note of E, which is F, isn't black. It's white. So the pattern of black, disallowed notes doesn't match the original pattern.

In fact, no note which you might wish to put on top, other than C, gives exactly the same major scale pattern, which is, clockwise from the "top":

white-black-white-black-white-white-black-white-black-white-black-white

The only way to get the same pattern in a different major key is to rotate the note names as a group, but not the circle itself. Leave the pattern-giving circle alone.

Here's what I mean. Say you want F on top as the tonic note of the (you guessed it) F major scale. Just rotate the note names, all by themselves as a group, seven positions clockwise:

Notice now that one of the piano's white keys, B, is no longer allowed, as it was in the key of C major. Instead, the black key known as Bb (or A#) is included in the F major scale. Notice, accordingly, that the black-white pattern of the octave circle is not necessarily that of the piano keys used for a given major key. In fact, C major is the only major key for which the black segments of the octive circle exactly match the black keys of the piano keyboard. (True, there is one minor key, A minor, that exactly matches the keyboard and thus uses only white keys ... but I'm not discussing minor keys here, only major ones.)

Notice now that one of the piano's white keys, B, is no longer allowed, as it was in the key of C major. Instead, the black key known as Bb (or A#) is included in the F major scale. Notice, accordingly, that the black-white pattern of the octave circle is not necessarily that of the piano keys used for a given major key. In fact, C major is the only major key for which the black segments of the octive circle exactly match the black keys of the piano keyboard. (True, there is one minor key, A minor, that exactly matches the keyboard and thus uses only white keys ... but I'm not discussing minor keys here, only major ones.)Of course, there's no law against including an unflatted B note in a tune written in the key of F major — but to do it in music notation, you have to put a natural sign before the note. Then, in playing the tune on a piano, you strike the B key (white) instead of the Bb key (black).

Rotating the note names as a group, while leaving the octave circle alone, you can in this way come up with twelve different major keys. The set of allowed notes in each are different, and unique. Here's Db major:

Now five of the notes in the C major scale have been flatted: D, E, G, A, and B have become Db, Eb, Gb, Ab, and Bb.

Now five of the notes in the C major scale have been flatted: D, E, G, A, and B have become Db, Eb, Gb, Ab, and Bb.So the actual notes which are "allowed" in a given major scale differ from one scale to the next. Yet the black-white pattern remains the same.

This distinctive black-white pattern is picked up by the ear after only a few notes are played, allowing the ear to "figure out," unconsciously of course:

- that the scale is indeed a major scale — not, say, a minor scale, for which the black-white pattern of the octave circle is different

- that the scale's root note or tonic is ... whichever note it happens to be (C in the first example, F in the second, Db in the third)

- which other notes are "allowed" in this major scale, and therefore which notes are not allowed

The "allowed" notes in the scale are also typically the "allowed" notes in the chords to which the melody is customarily set. For example, when a measure of a C major melody features the notes of C and E, often the associated chord played on a guitar or piano will be the C major triad of C-E-G. If G and B are being emphasized in the measure in question, possibly the associated chord will be the G major triad, G-B-D.

Accordingly, the G minor triad of G-Bb-D will usually not be heard in the harmony accompaniment for a C major melody. Why? Because Bb is not one of the "allowed" notes in the C major scale.

By the same token, G-Bb-D will crop up in melodies written in the key of F major, while the G-B-D triad is considered odd. Why? Because Bb is a part of the F major scale, while unflatted B is not.

Thus, an awful lot of wisdom about keys, scales, and associated chords derives from the simple fact that the disallowed (in the octave-circle diagrams, black) notes of a major key — and this is true, in a like way, also of a minor key — are not evenly or symmetrically distributed around the octave circle.