Let's All Play: "A Hard Day's Night"

The Beatles: Rock Band is here as of Sept. 9. In the videogame, you don't play chords on a real guitar. Still, as the chords unfold in the real music heard in the background, the Rock Band player can mimic them by pressing buttons on a guitar-shaped game controller. It feels like making music.

The Beatles: Rock Band is here as of Sept. 9. In the videogame, you don't play chords on a real guitar. Still, as the chords unfold in the real music heard in the background, the Rock Band player can mimic them by pressing buttons on a guitar-shaped game controller. It feels like making music.Like all pop, the Beatles' music is built on chords. To find out what chords the Beatles play on any given song, check out The Beatles Complete Chord Songbook. Hint: click on the image above to find the book on Amazon, then activate Look Inside! by clicking on the picture you see there of the book. Six clicks on a right-pointing arrow later, and you'll be looking at the words and chords of one of the most canonical of the Beatles' songs: A Hard Day's Night.

A Hard Day's Night was important. It was the title song of the 1964 movie of the same name. The movie came out just after the Beatles initial flush of popularity had begun to ebb. If the movie had fizzled, who knows whether the Beatles would have, too? But the movie was a huger hit, and so was its title song.

The song A Hard Day's Night has two verses at its start, then a middle section ("When I'm home ..." etc.). Then the first verse repeats, followed by a brief guitar instrumental that leads into a repetition of the end of verse 2. Next, the middle section makes its second appearance, followed by verse 1 all over again. When that redo of verse 1 ends, we start to hear an outro that begins "You know I feel alright/You know I feel alright" — and then, as the music fades out, we hear no more singing, just an endlessly repeated pair of chords on John Lennon's rhythm guitar, accompanied by arpeggiated notes on George Harrison's lead guitar, along with a single repeated note on Paul McCartney's bass.

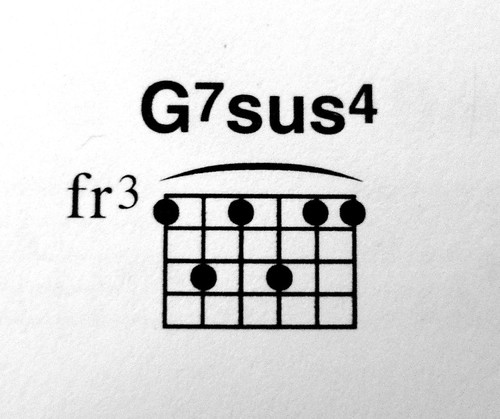

Ignore, for now, the G7sus4 chord at the very beginning of A Hard Day's Night. It's one of the most celebrated chords in all of rock history, and one of the most controversial. (Hear it by clicking here.) As I'll go into later, there are any number of expert opinions as to exactly what chord it actually is; the G7sus4 designation in The Beatles Complete Chord Songbook is just one opinion. This chord sounds before the first verse actually begins. So, strictly speaking, it's not part of the first verse.

If you factor out that first chord, the rest of the first verse has the same chords as verse 2 has — and as each of the two later repetitions of verse 1 has. (In fact, the guitar instrumental that leads into the repeated tag end of verse 2 uses those very same chords as well.) These verses' chord sequences all begin G-C-G-F-G. If you look at verse 1 in particular, those five chords correspond to "It's been a hard day's night/and I've been working like a dog."

The next section of the verse, "It's been a hard day's night/I should be sleeping like a log," is exactly the same, chord-wise (as long as you assume the G chord that ends the first section is held over — it continues to be played — to begin the second part of the verse).

Making that same holdover assumption, the chords for "But when I get home to you/I find the things that you do/Will make me feel alright," the final section of verse 1, likewise begin with G-C. But then comes a surprise: the next four chords are D-G-C7-G. The D chord, at "things ... ," is new. It hasn't been heard before.

Dominant Seventh Chords C7 means a C Major chord with an added note: specifically, the seventh note in the C Major scale, but lowered or flattened in pitch by a half step. In C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C, which is the entire C Major scale, it is the note B that is the seventh note. The C Major chord is C-E-G, so the C7 chord is C-E-G+B flat. The use of the flattened seventh note, B flat, makes C7 a "dominant seventh" chord rather than a "major seventh" chord. |

I'll put a chord in parentheses to show that it's a holdover or re-sounded chord, by the way. The full set of chords for the first verse (and every other verse) is, accordingly, G-C-G-F-G//(G)-C-G-F-G//(G)-C-D-G-C7-G. (The // simple divides the sections of the verse from one another.)

What about the verse that begins as an instrumental and then tacks on the final part of verse 2? It's full set of chords is, again, G-C-G-F-G//(G)-C-G-F-G//(G)-C-D-G-C7-G! The only real difference is that George Harrison is playing a lead guitar solo while John Lennon briefly leaves off singing. (George's solo is interesting because it does not simply repeat the melody John had been singing.)

All told, there are just five chords in each (vocal or instrumental) verse, though many of them are repeated. The five are G, C, F, D, and C7. And C7 is just an embellishment of the C Major chord, C.

Basically, then, the verses of A Hard Day's Night use only four little stations on the vast railroad of possibilities: G, C, F, and D.

Now we come to the middle section of A Hard Day's Night ("When I'm home ... feeling you holding you tight, yeah"). The two repetitions of this middle section are both just alike; songwriters speak of such a middle section as a "middle eight," since each repetition of the middle section uses exactly eight measures or bars. Two other names for the middle eight are the "bridge" and the "release."

Minor Chords Bm is the designation for the B minor chord, in musical notation, while Em is the E minor chord. In minor chords, the second note in the chord is lowered a half step in pitch. So Bm uses the notes B-D-F sharp, not B-D sharp-F sharp. Em likewise has its second note lowered, from G sharp to G. |

The D7 Chord Analogously with the C7 chord, D7 is the D Major chord, D-F sharp-A, with the lowered seventh note of the D Major scale, C (rather than C sharp), added to it. In the D7 chord, the note C is considered a lowered or flattened note because the actual seventh note in the D Major scale (D-E-F sharp-G-A-B-C sharp-D) is C sharp. |

Middle-Eight Key Changes In popular music it is customary to write the middle eight in a different key from the rest of the song. Specifically, the key of the middle eight is (typically, but not always) the "dominant" of the original key. The dominant note of any key is its fifth note: the fifth "degree" of the scale of that key. Take the key of G major, whose scale is G-A-B-C-D-E-F sharp-G. Count off from the left, with G being 1, A being 2, etc. What note is note 5? That fifth-degree note is ... D! So the note D is the dominant in the G Major scale. |

When a song, such as A Hard Day's Night, which is in the key of G Major changes key for its middle eight, the key that it changes to will (usually) be the major key of the dominant — in this case, D Major. And in fact A Hard Day's Night's middle eight is in the key of D Major.

Let's get back now to the chords used in the middle eight of A Hard Day's Night. The Bm chord, B-D-F sharp, is the chord built on the sixth note, B, of the D Major scale, a scale which in its entirety reads D-E-F sharp-G-A-B-C sharp-D. The Em chord, E-G-B, is the chord built on the second note, E, of the D Major scale. The D7 chord, D-F sharp-A-C, is the dominant seventh chord built on the first note, or root, of the D Major scale. In other words, Bm, Em, and D7 are all chords that you would expect to hear when the key is D major.

Meanwhile, the G, C (or C7), and D of the verses are chords that one expects in the key of G Major. They are built on that key's first or root note, its fourth note, and its fifth note, respectively.

Only the F chord of the verses stands out as not really belonging to the scale of G major. In the first verse, it arrives on the first syllable of " ... working like a dog" and again on the first syllable of " ... sleeping like a log." In each case, the second syllable, "-ing", is sung in John Lennon's lead vocal as the note F natural — that is to say, the F sharp that rightly belongs to the key of D Major is lowered a half step in pitch. John, who wrote the song, put in the F chord and the F natural note because they give us a little shock when we hear them. It's a perfect choice: the lyric at the point of arrival of the F chord wants a special emphasis, and the unexpected F chord delivers it.

Now, what about the famous chord that starts off the whole shebang, G7sus4 ... or whatever the correct designation actually is? Therein lies a tale.

I'm following The Beatles Complete Chord Songbook in saying the chord is a G7sus4, but click here to see how certain real experts analyze the chord. (Warning: this section from Wikipedia's article on the song is basically over my head and may be over yours as well.)

G7sus4 on a Guitar

The strings of a guitar are tuned to the notes E-A-D-G-B-E, starting with the leftmost string in the illustration above, with the rightmost string's E being pitched two octaves above the sixth or leftmost string's E. (The rightmost string in the illustration at left corresponds to the bottommost string of the guitar and is counted as the guitar's first string. The leftmost string in the illustration corresponds to the topmost string of the guitar and is the guitar's sixth string.) G7sus4 is how The Beatles Complete Chord Songbook designates the chord. It's made on a guitar with fret three, counting from the end of the guitar neck, being barred with the index finger and with other fingers pushing down the third and fifth strings (counting from the right in the illustration below) at a point two frets further inward, at fret five. (There is at least one other way to play G7sus4 on a guitar, but this is the way that The Beatles Complete Chord Songbook uses.) |

In G7's G-B-D-F, each successive note (except of course for the first note) is higher than the previous note by an interval called a "third." The interval between G and B passes through G sharp, A, and then B flat on its way to B, so it brackets a total of four half steps. When an interval of a third brackets fully four half steps, it's a "major third." But from B to D there are only three half steps: B-to-C, C-to-C sharp, and C sharp-to-D. So that interval is a "minor third," not a major third. And the D-to-E flat-to-E-to-F interval at the top of the G7 chord is, likewise, a minor third.

Most chords are made by stacking thirds, whether minor or major, atop one another; mostly, the many different varieties of chords arise from deciding whether each third that is to be used will be a minor third or a major third. But G7sus4, because it is a "suspended fourth" chord, is different. Raising the B in G7's G-B-D-F to a C produces G7sus4's G-C-D-F ... at the expense of making the first interval, the one from G to C, wider than a major third.

In fact, it is that interval, spanning five half steps, that is called a "perfect fourth." The note C is a perfect fourth above the note G. G7sus4 is not a chord that consists of stacked thirds — no suspended-fourth chord is.

A suspended-fourth chord creates suspense. G7sus4 wants to resolve to, for example, a G7 chord ... which isn't quite happy, either, as G7 has an inner tension that makes it want to become a plain G Major chord (or else pretend it is the dominant seventh chord built on the fifth note of the C Major scale, which is G, and resolve to a C Major chord).

In A Hard Day's Night the opening G7sus4 turns into, guess what? The standard G Major chord which begins the first verse.

Labels: The Beatles