The Scots-Irish and Country Music

As far as I can tell from what I know of my family tree, I am partly of Scots-Irish descent. As I wend my way into my early 60s, I find more and more that I love the music of my people in America — country music.

I wrote about my Scots-Irish roots a while back in Long Live the Scots-Irish! and, on a more personal level, in My (Nonexistent) Redneck Bar Mitzvah. Senator James Webb of Virginia, likewise Scots-Irish, wrote a 2005 non-fiction bestseller called Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America to document who the Scots-Irish are and why it matters.

I wrote about my Scots-Irish roots a while back in Long Live the Scots-Irish! and, on a more personal level, in My (Nonexistent) Redneck Bar Mitzvah. Senator James Webb of Virginia, likewise Scots-Irish, wrote a 2005 non-fiction bestseller called Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America to document who the Scots-Irish are and why it matters.Now I'd like to revisit the subject and tell why it matters to lovers of country music specifically.

First of all, the term Scots-Irish is often spelled "Scotch-Irish." The two terms are interchangeable (even if some say that "Scotch," spelled that way, is an appropriate name for whiskey, not people).

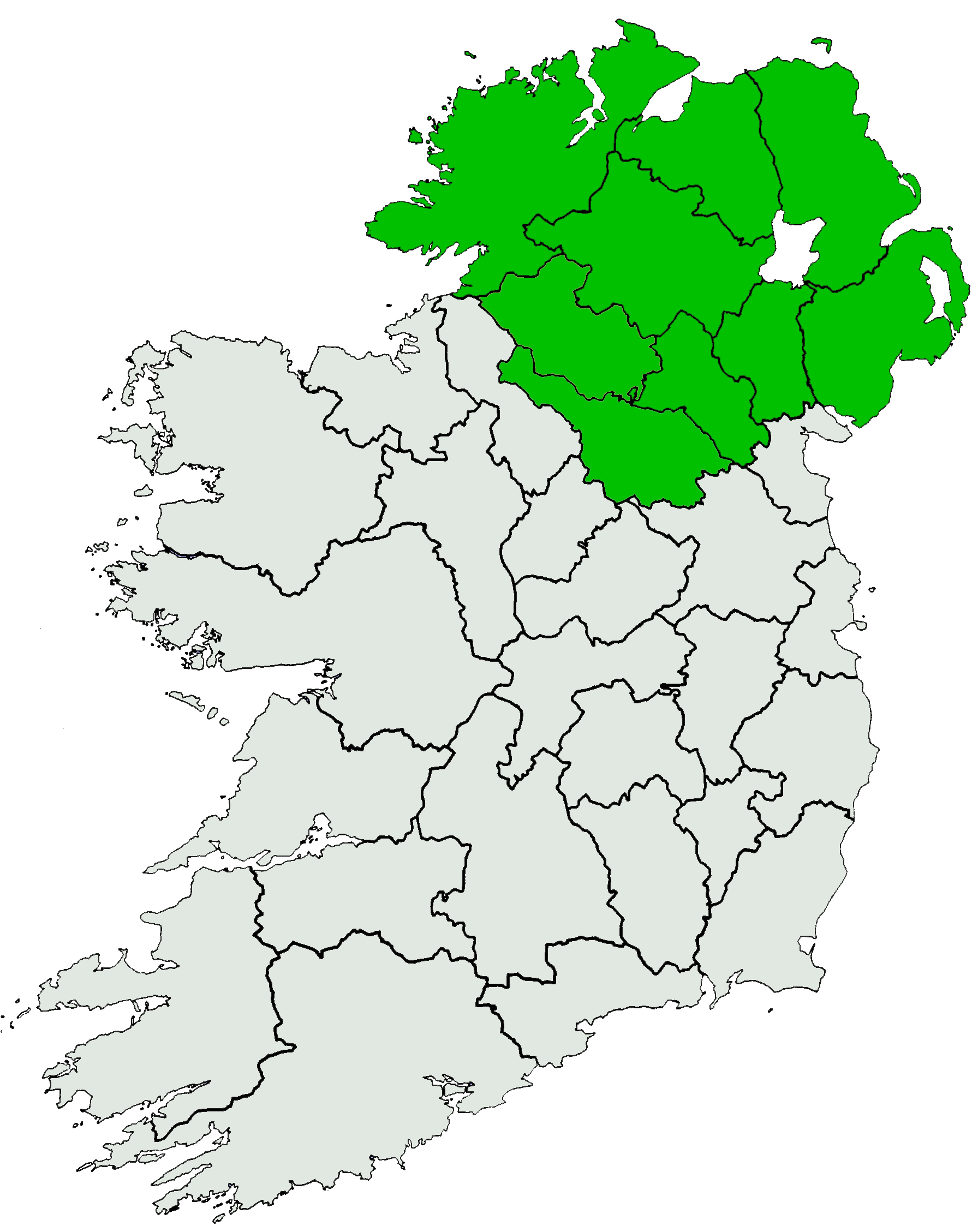

Furthermore, "Scots-Irish" is a term you hear only in America or Canada; in the Old World the same group of people are called mainly "Ulster Scots," Ulster being the northernmost of Ireland's four provinces:

Most of the counties in Ulster constitute what we know as Northern Ireland, the Irish part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. (The rest of Ulster's counties are in the larger Republic of Ireland to Ulster's south. And the rest of the United Kingdom is composed of England, Scotland, and Wales, the once-separate countries that occupy the big island to Ireland's east, Great Britain.)

The majority of Ulstermen were North Britons: their ancestors came to Ireland during the 1600s from what would, in 1707, under Queen Anne, become the union of England, Scotland, and Wales. Starting a century before, in 1606, the British monarch James I (James VI of Scotland) decided he needed to pacify and civilize Ulster, which belonged to the British crown but was filled with rebellious Gaels — as Irishmen were called back then. Remedy: send over to the "Plantation of Ulster" a bunch of the most equally troublesome North Britons the king could find and have them quash the native Gaels.

Those transplanted North Britons of the 17th century were mainly from the Scots Border country, the area on both sides of the border where England meets Scotland. In the prior century, the 16th, they generally did not adhere to the newly established Protestant churches of England or Scotland. According to this page on "Religion and the Scottish Temper":

The Border [people] were nominally Catholic — most Scots were still Catholic in the 16th century — but notoriously irreligious. That soon changed. Once the Borderers were banished to Ulster, they embraced the Presbyterianism of [founder] John Knox. They [later] brought their fierce religiosity to America, where they applied it to the Methodist and the Baptist faiths as well.

However religious they were, the Borderers were born troublemakers in other respects ... so much so that after they had been in Ulster for a century or so, the British throne decided it had to clamp down on them, and many of the harried Ulstermen decamped for America in the New World.

"Borderers" is an apt name for them. Border Scots in King James's time had for centuries been pretty much indistinguishable from Border English, as over the course of many (mutually hostile) centuries there had been repeated wars between Scotland and England, and the exact location of the border kept shifting. The families or clans who lived near the border bore much of the collateral damage of the fighting and got little in return. Which throne they had to swear fealty to at any given time came to mean little to them, as the border's position kept changing anyway. To keep afloat, various Border families would habitually raid the lands of their counterpart families on the other side of the current fealty divide. Then, in increasing economic desperation, they started raiding the lands of families on their own side of the divide.

Over time, these raiders or "Border Reivers" (depicted below heading out on a raid) became increasingly lawless ... or, actually, they developed their own private version of the law. There were, for example, rules which governed how many days could elapse (no more than six) after they had endured a raid, while a counter-raid was in the making.

In America, centuries later, whole clans of the Borderers' born-fighting descendants would likewise conduct "family feuds," according to unwritten rules. Outsiders would call it anarchy.

The majority of those descendants, as they became the "Scots-Irish" in America, arrived on these shores between 1717 and 1775, the year when the American Revolution began. Their original mission, early on, was to help settle and secure the frontier that separated Indian-inhabited inland/mountain territory from the (mostly Puritan) English colonies of coastal New England. As such, the original Scots-Irish were invited here by the likes of Puritan minister Cotton Mather of Boston, who was not Scots-Irish and did not share the Scots-Irish preference for Presbyterian religion.

So the Puritans and the Ulstermen couldn't get along, ultimately, in part because the latter couldn't stand the idea that they ought to, like the Puritans, have their religion specified to them by acknowledged civic authority. The original Scots-Irish were in no way civic, and they quickly became personae non gratae in the coastal settlements.

Most of them willingly moved away from their original entry point — later on during the migration, it shifted from New England to mainly Philadelphia — as, ranging as far south as the Carolinas and northern Georgia and Alabama, they inhabited the American backcountry: the foothills and mountains of Appalachia.

Best I can tell, they were joined there by other Borderers whose families had never sojourned in Ireland. These were the descendants, living in their original Border-country homeland, of the same Borderer families that had in earlier times become Ulster Scots. (And they were also joined in America by various other dissident religious groups; the famed Scots-Irish frontiersman Davy Crockett was part French Huguenot.)

Those of the early "Scots-Irish" who were actually descended from Anglo-Scots Borderers (again, as best I can tell) ethnic Celts, just as were the true Ulster Scots. Historically, Celts are the speakers of any of a certain distinctive group of ancient European languages. The Celts' forebears, before they arrived in the British Isles, lived in continental Europe. Originating in central Europe during the prehistoric Iron Age, over a period starting about 1200 BC and lasting until Roman times in the 1st century BC, the Celts were peoples who spread their advanced (if pre-literate) culture to the Black Sea and modern-day Turkey to the east. Westward, they fanned out to what are today Spain and Portugal, France, the Low Countries, southern Germany ... and the British Isles.

Then, from 300-700 of the Christian era, during the late Roman period and early Dark Ages, European peoples speaking Germanic rather than Celtic languages pretty much extinguished Celtic culture on the continent of Europe. Some of these ethnic victors were the well-known Angles and Saxons. They, along with Frisians and Jutes, would one day extend their conquests to the island country that would come to be called, after the conquering Angles, "Angle-land" or England.

But the Celtic denizens of the British Isles would continue their rule over the parts we today know as Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and Cornwall. And neither would those Celts who continued dwelling in the north part of what then was on its way to becoming "England" readily knuckle under to the conquering Anglo-Saxons.

Predominately, the Celts in Ireland and in the highlands of northern Scotland were Gaels. Gaels are one of the two main Celtic subdivisions, the other being Brythons. (In those times, in fact, the Gaels in Scotland and in Ireland considered themselves one people, called Scoti by the Roman occupiers of Britain, who feared their raids and who, unable to subdue them, built Hadrian's Wall to keep them out.)

By medieval times, the Celts in Cornwall, in Wales, and in the Scottish lowlands and border regions were Brythons, not Gaels. The Brythons were the Celts who donated their name, slightly transmogrified, to that pre-Anglo Saxon realm still referred to today as Britain. King Arthur, if he was a real person, was a Brython. The Brythons were also the indigenous people of Brittany, in France.

In the map below showing, along with Brittany in France, 5th-century A.D. Britain and Ireland, the Brythonic kingdoms have black names. Most of those kingdoms that are part of today's England would soon give way to the invading Germanic peoples. The blue-named regions in modern Ireland and Scotland are those of the Gaels, a.k.a. Irish, whom the Romans had called Scoti or Scots. These regions are also called "Goidelic," since "Goidels" is another name for Gaels. The regions with names in brown belonged to the ancient Picts, who may or may not have been Celts (no one is quite sure), and who would later give way to the Scots. The various Germanic peoples already held the areas whose names are in red.

So the Scots-Irish in America were predominately descended from a hill folk whose erstwhile cultural centers in southern Britain had been pushed to the north of Britain by the Anglo-Saxon conquerors. Once the Borderers arrived in what would thereafter become their traditional north-country homeland, they remained squeezed between the Gaels (some of whose own traditional lands north of Hadrian's Wall they had usurped) along with the increasingly urban Scottish lowlanders (as we call them today) to their north and, on their other side, the Germanic peoples to their south.

Here is where things get a bit confusing, terminology-wise. The Scots-Irish are often said to be derived, specifically, from Scots lowlanders: inhabitants of the Scottish Lowlands, that is, as distinct from those Scots living in the Scottish Highlands. But the homeland of the Scots-Irish is more properly thought of as the Scottish Southern Uplands, as distinct from the Scottish Central Lowlands.

The Southern Uplands was not "lowland" country of low geographic elevation, but rather Old World hill country — in topography not unlike much of the backcountry which they would take to so readily in the New World.

In the valley areas of the Central Lowlands of Scotland are today found the great cities of Edinburgh, the Scottish capital, and Glasgow. In common with the Border Scots of the Southern Uplands, in the wake of the Anglo-Saxon conquest the people in these valleys no longer spoke a Celtic language; today those north of the Anglo-Scots border natively speak the variety of English known as Scots, immortalized by Scotland's great national poet Robert Burns. Scots is of course a cousin of Anglo-Saxon English. The Scots-speaking Central Lowlanders developed a more urbane culture that was unlike that of the clan- or family-oriented Southern Uplanders who dwelt closer to (and across) the English border.

The Border Scots who first became Ulster Scots and then, in America, became the Scots-Irish were anything but urbane. Though they bore intense loyalty to their own clan chiefs, these herders and hardscrabble farmers were also fighters and raiders who were congenitally unable to truckle to any distant lord or king or church. Their fierce progeny, once they arrived in the New World, would be ideal for subduing the vast mountain area to the west of the coastal townships of colonial New England, beyond the incipient cities of colonial Pennsylvania and the plantations of tidewater Virginia.

These ideal frontiersmen remained an indomitable folk, and it would be their culture that would, during Prohibition times in the 20th century, provide Americans in general with hard moonshine liquor. Later, the bootleggers' speed-oriented, automobile-based distribution system would develop into NASCAR racing, and many bootlegger descendants would become today's good-buddy truckers exchanging calls on their CB radios, dodging smokeys, and powering America's interstate commerce in their semis/eighteen-wheelers.

The original Scots-Irish in America did not call themselves that. If asked at all, they said they were "Irish," since they had migrated to America from Ireland. When the 19th century brought waves of other Irish immigrants, starving folks fleeing the Potato Famine, there needed to be a distinction drawn between the new arrivals, predominantly Catholic, and the earlier-arriving Protestants who likewise styled themselves "Irish."

The Protestant "Irish"/Ulster Scots who came here during the pre-Revolutionary 1700s, and were joined here by Border Scots and other Dissenters whose families had never touched Irish soil, were little concerned with nomenclature, though; they were too busy eking out a living in the Piedmont foothills and in the high Appalachian mountains themselves, and then migrating westward through the likes of the Cumberland Gap ...

... to push the American frontier westward toward the Mississippi River and on to the Pacific.

They may not have realized it, but their freewheeling culture was the lineal descendant of the lawless border culture of the Border Scots and North Britons whose genes they bore westward into the frontier lands of the New World. On the frontier with them were Dissenter peoples of other than North British ethnicity, such as French Huguenots and German Palatines. The Ulster Scots per se had, in Ireland, become Presbyterians who nevertheless resisted the interference of the established Presbyterian Church of Scotland. All of the religiously dissident groups who made up the Scots-Irish, broadly defined, were Calvinist, but in America their religious affiliations would tend toward the Evangelical denominations, particularly Baptist and Methodist.

Whether through intermarriage or simply due to the fact their originally Border Scots culture was ideally adapted to frontier life in America, it was that culture of self-reliance and "lawless" indomitability that spread ahead of and immediately behind the advancing American frontier.

When census takers and demographers of the present day find that people of Scots-Irish ancestry are more heavily represented in such portions of the United States as the "Upland South" than in many other areas of the country, they are referring to the area shaded green in the map above. It includes the Southern Appalachians and Piedmont; the Ozark Plateau of Missouri and Arkansas, which extends into Oklahoma and nicks the southeast corner of Kansas; and the Ouachita Mountains, which are in west central Arkansas, southeastern Oklahoma and north-east Texas.

The Ozarks and the Ouachitas are, collectively, designated the "Interior Highlands" of the U.S. The many plateaus and hills between the Appalachians and Ozarks, such as the Cumberland Plateau and the Allegheny Plateau, are also part of the Upland South, so the denizens of the Upland South are still, as ever, hill people.

But not all of the area shaded green in the map above are hills and highlands. For instance, the Nashville Basin in Tennessee and the Bluegrass Basin around Lexington, Kentucky — among other geological lowlands — are part of the region designated the Upland South, and also were largely settled by Scots-Irish and their ilk.

In other words, the culture born in the Southern Uplands of the Scottish-English border came to predominate in the (mostly) hilly region called the Upland South in this country, as the people who carried their hill/border culture from North Britain to Ulster to the U.S. spread throughout our earliest frontier communities.

Descendants of the original Scots-Irish are today heavily represented also (see the map above) in the American Northwest and in parts of Texas, Colorado, and California.

You can't necessarily tell whether you're Scots-Irish by looking in your family tree for surnames that begin with Mc or Mac. First of all, those prefixes apply to many Irish Catholic families who came here in the 1800s; the Scots-Irish were Protestants. Second, when we're talking about Scots names specifically, not Irish, those prefixes tend to apply to names of Scottish highland clans.

MacLeod, MacDonald, MacLean, and the like are names of clans from the area of the map above that is shaded darker green. These are the highlands of Scotland, and they are not, for the most part, where the American Scots-Irish started from. (Many of the highland clans, such as Clan Campbell — I myself have Campbell ancestry — have surnames not prefixed with Mc/Mac, adding to the confusion.) But the major clans of the Scottish Southern Uplands are entirely without Mc/Mac prefixes: Douglas, Elliot, Scott, Johnston, Kerr, and so on. One of my own ancestors was an Armstrong, by the way, a good Border Scot name.

Those are names that look and sound English, to my eye and ear. But they're really Scots-Irish.

According to a Wikipedia article on Border Reivers, a partial list of important families whose original homeland straddles the Anglo-Scottish border, whether on the Scots side or on the English side, includes: Hume, Trotter, Dixon, Bromfield, Craw, Cranston, Forster, Selby, Gray, Dunn, Burn, Kerr, Young, Pringle, Davison, Gilchrist, Tait, Scott, Oliver, Turnbull, Rutherford. Armstrong, Croser, Elliot, Nixon, Douglas, Laidlaw, Turner, Henderson, Anderson, Potts, Reed, Hall, Hedley, Charlton, Robson, Dodd, Milburn, Yarrow, Stapleton, Fenwick, Ogle, Heron, Witherington, Medford, Collingwood, Carnaby, Shaftoe, Ridley, Stokoe, Stamper, Wilkinson, Hunter, Thomson, Jamieson, Bell, Irvine, Johnstone, Maxwell, Carlisle, Beattie, Little, Carruthers, Glendenning, Moffat, Graham, Hetherington, Musgrave, Storey, Lowther, Curwen, Salkeld, Dacre, Harden, Hodgson, Routledge, Tailor, Noble. Of course, if your name is Rutledge and not Routledge, for example, or Beatty and not Beattie, you can consider it identical and thus bona fide Scots-Irish.

There are the numerous other Scots-Irish surnames, too many to list, whose historical importance in their land of origin, Britain, is not perhaps as great. You or your ancestors may possess one or more of them. Unfortunately, official records do not seem to exist of the surnames of the early Scots-Irish immigrants who came originally to New England. But Ulster presbytery and synod records from the period 1691-1718, just before the migration to America began, do exist. You can look up family-tree surnames at the Lynx 2 Ulster website here to see if they might be Scots-Irish. (Don't be discouraged if you don't find the name you are looking for. The list isn't exhaustive. Also, the name you are looking up might be that of a non-Scots-Irish male ancestor who married a Scots-Irish wife, and thus had half-Scots Irish progeny.)

In this country, President Andrew Jackson was Scots-Irish, as were President Ulysses S. Grant, President Bill Clinton, and WWII General George S. Patton ...

... as was his portrayer in movies, George C. Scott. Arizona Senator John McCain is Scots-Irish (yes, some Scots-Irish Americans do wind up with a Mc/Mac prefix to their surnames).

Just as you cannot easily tell by its Mc/Mac form whether a given surname in your family tree is Scots-Irish, your family's religious heritage is not necessarily a clue to Scots-Irish ancestry. The bulk of the original Scots-Irish immigrants were Presbyterian — though dissenters to the (by their reckoning) oppressive hegemony of the established church in Scotland — in America they often became Baptists or Methodists. According to the Wikipedia article on the Scotch-Irish American, the establishment of many settlements in the remote back-country put a strain on the ability of the Presbyterian Church to meet the demand for qualified, college-educated clergy that were insisted on by that highly organized church. Religious groups such as the Baptists and Methodists had no higher-education requirement for their clergy, and these groups readily offered ministers to meet the demand of the growing Scots-Irish settlements. By about 1810, Baptist and Methodist churches were in the majority among the Scots-Irish, and the descendants of the Scots-Irish today remain predominantly Baptist or Methodist. Today's Bible Belt Evangelicals are, culturally and often ethnically, the heirs of yesterday's Scots-Irish frontier folk.

The original Scots-Irish first took over Appalachia, in what would become the United States. Some then moved westward and brought their culture to the rest of the Upland South and beyond, while others stayed behind.

Some of the ones that stayed behind got stuck in a cultural time warp and, come the 20th century, came to be called "hillbillies" and "hicks." These are the working-class poor of Appalachia, the coal miners and subsistence farmers whose plight has become well known today.

Other working-class descendants of the original Scots-Irish have hailed from the broader Upland South and elsewhere. To them and to their Appalachians cousins more than anyone else country music owes its very existence.

The first commercial recording of country music was "Sallie Gooden" by fiddlist A.C. (Eck) Robertson ...

... in 1922 for Victor Records. Robertson was born in Delaney, Arkansas, not far from the Ozark National Forest. I assume he was ethnically or culturally of Scots-Irish stock.

Among the first country stars were Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family, whose songs were first captured at a historic recording session in Bristol, Tennessee, on August 1, 1927, where the famed Ralph Peer was the talent scout and sound recordist. Rodgers, the Singing Brakeman, was probably born in Geiger, Alabama, at the edge of the Southern Uplands. The Carter Family hailed from southwestern Virginia, in the Appalachian Mountains. Again, I assume that the names Rodgers and Carter count as Scots-Irish surnames.

According to this list of Scots-Irish Americans, country/rockabilly/bluegrass notables Johnny Cash, Billy Ray Cyrus, Loretta Lynn (born Loretta Webb), Crystal Gayle (Loretta's younger sister, Brenda Gail Webb), Merle Haggard, Faith Hill (born Audrey Faith Perry), Alison Krauss, Reba McEntire, Dolly Parton, Elvis Presley, Charley Pride (an African-American!), Ricky Skaggs, Hank Williams, and Tammy Wynette (born Virginia Wynette Pugh) are of Scots-Irish lineage.

According to Elizabeth Semancik, who created Albion's Seed Grows in the Cumberland Gap — the Cumberland Gap is located along the Wilderness Road in the Appalachian Mountains where the Virginia state line daggers its way into the border between Kentucky and Tennessee — "Music in the Cumberland Gap Region reflects the Anglo-Scotch border influence quite strongly. In style of performance, genre, and instrument selection, the Cumberland music strongly exhibits roots in the [North British] borderland from whence its people [originally] came." (See Semancik's Music section.)

Semancik took some of her material from historian David Hackett Fischer's Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America. One of Fischer's four "folkways" was that of the Border people of North Britain.

Semancik took some of her material from historian David Hackett Fischer's Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America. One of Fischer's four "folkways" was that of the Border people of North Britain.The Border people, says Semancik, brought ballads and fiddle music with them to America. As "a folksong that tells a story, usually in extremely condensed fashion," an old ballad such as "The Brown Girl" or "Barbara Allen" — or a "riddle ballad" such as "I Gave My Love a Cherry" — was originally sung without instrumental accompaniment or ostentatious vocal flourishes, though it was "discretely embellished by vibrato and grace notes." Country music today — check out anything by Reba McEntire — is often, we ought to keep in mind, full of vibrato and grace notes.

The singing of "Barbara Allen" in the video below is not like the centuries-old original ...

... since it's sung in a major scale. Five sharps in the key signature = the key of B major; the tonic note (here, B) begins and ends each verse, and the other notes that are used all come from the DO-RE-MI•FA-SOL-LA-TI•DO scale based, in this particular case, on B as DO. (• represents a half step in pitch between, for example, MI and FA, while - represents a whole step between, for example, SOL and LA. See "Modes" below.)

The first (and every) verse's notes are 1-3-4-5-4-3-2-1 / 2-3-5-8-8-7-5 // 7-8-6-4-5-6-5-3-1 / 2-3-5-6-5-3-1, where 1 is DO, 2 is RE, 3 is MI, etc., up to 8, which is DO an octave up. Every note in the scale is used.

But "ballads often have a haunting, plaintive sound," according to Semancik, "because they are based on modal scales which do not correspond to modern major and minor scales."

Modes There are several modal scales, or modes. For example, MI•FA-SOL-LA-TI•DO-RE-MI is called Phrygian mode. A song in B Phrygian mode begins and ends on (in this case, B as) MI, not B as DO. The difference lies in which scale steps turn out to be whole steps and which are half steps. A whole step is the "pitch distance" between any two white keys on the piano keyboard that have a black piano key between them, such as C to D (with C-sharp in between) or F to G (with F-sharp in between). A half step is the pitch distance between any two white piano keys that lack an intervening black piano key, such as B to C or E to F. A half step likewise exists between any white piano key and its adjacent black piano key, such as E-flat to E or C to C-sharp. In general, any two piano keys of whatever color are a whole step apart if there is exactly one piano key of any color between them; if there's no piano key between them, they're a half step apart. In MI•FA-SOL-LA-TI•DO-RE-MI, which is the pattern for the Phrygian mode, the step from 1 to 2 (MI to FA) is a half step, while in DO-RE-MI•FA-SOL-LA-TI•DO, the major scale, the step from 1 to 2 (DO to RE) is a whole step. Why? If B is the tonic note in MI•FA-SOL-LA-TI•DO-RE-MI, MI to FA (the first two notes in the pattern) is represented by B to C, and there's no intervening piano key. But if B is the tonic in DO-RE-MI•FA-SOL-LA-TI•DO, DO to RE, the first two notes in the pattern, is represented by B to C-sharp. There's an intervening piano key: C. Putting the half steps at different places in the pattern than the standard major scale does, the different musical modes give music a quaint, quirky feel. Likewise, the (melodic) minor scale in use today and also in the music of yore puts one of its half steps at a different place than the major scale does (between RE and MI, not MI and FA): DO-RE•MI-FA-SOL-LA-TI•DO. Pentatonic Scales The old ballads would often use a major pentatonic scale rather than a modal scale. A major pentatonic scale uses just five notes: DO-RE-MI__SOL-LA__DO, with the second DO tacked on the end to complete the octave. The __ between MI and SOL and between LA and DO means that there are three half steps in the interval. This major pentatonic scale can also be thought of as omitting FA and TI from the usual DO-RE-MI•FA-SOL-LA-TI•DO major scale. |

Do you hear how the melody has turned "country"? I'll bet it's more like the original as sung by the Borderers, for "Barbara Allen" was converted in the first rendition above from a major pentatonic scale to a "diatonic" major scale. The latter scale is familiar to us today, but it is quite unlike how the Borderers originally sang the ballad.

Labels: Country Music

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home